Women’s Orgasm Experiences Through Virtual Bodysex

Women’s Orgasm Experiences Through Virtual Bodysex® Workshops

Covid lockdown happened on the heels of our Goop episode. We'd received thousands of emails, our workshops were booked with wait lists and then everything went dark. Betty was dying and I was making healthcare decisions over the phone.

With a broken heart, I put together "virtual Bodysex" drawing upon my workshop experience, concepts Betty had impressed upon me, and a desire to hold space for women during this difficult time.

I worked with 400 women in 40 countries/45 states from different cultures and backgrounds but with one shared desire: to connect to their orgasm. As I looked over my excel spreadsheet, I started to see patterns so I reached out to Debby Herbenick at the Kinsey Institute.

She had me complete research training and signed on to help me turn my data into research. Consent forms were sent out, personal information was redacted, and this paper was written by Callie Patterson. 132 women participated.

This research is my proof of the Betty Dodson method of self love and independent orgasm. This research is my call to action: we must teach our daughters about the female model of sexual response and support their sexual development through masturbation.

Carlin

INTRODUCTION

Pleasurable and satisfying sexual experiences are an important part of many people’s sexual health and wellbeing. Sexual pleasure has been associated with positive sexual functioning, greater frequency of orgasm, sexual communication, and safer sex intentions and behaviors, including increased condom use (Beckmeyer et al 2021a; Herbenick et al., 2018a; Klein et al., 2022).

However, women report less frequent orgasm, less pleasure, and more discomfort and pain during sex as compared with men (Boydell, Wright, & Smith, 2021; Mahar et al., 2020). Also, women with orgasm difficulty (compared to those without orgasm difficulty) generally report greater sexual inhibition and more negative cognitive distractions (e.g., about prior sexual abuse, poor body image) and fewer erotic thoughts (Moura et al., 2020).

Although experiencing orgasm is not important to all women, it is important to many women, who often consider “good sex” to include physical pleasure and, quite often, orgasm (Fahs & Plante, 2017). The orgasm imperative—which is the idea that orgasm is a necessary part of sex rather than one possible form of pleasure out of many—is pervasive both socially and within women’s sexual relationships (Potts, 2000).

Media and pornographic depictions of orgasm often reinforce the orgasm imperative alongside with the coital imperative—strengthening expectations that women will experience orgasm through vaginal-penile intercourse alone (Gavey et al., 1999). However, many women find it easier to orgasm through vaginal penetration alongside focused stimulation to their glans clitoris (Herbenick et al., 2018) or else through sexual activities such as stimulation with a vibrator or other sex toy, or through cunnilingus (Richters et al., 2006; Rullo et al., 2018).

Further, women often report experiencing pressure or coercion to orgasm during partnered sex (Chadwick & Van Anders, 2022). Because of these negative feelings, pressures, as well as for other reasons (e.g., to boost a partner’s confidence or to end sex), women are also more likely than men to report pretending orgasm as part of partnered sexual experiences (Herbenick et al., 2019; Muehlenhard & Shippee, 2010). Indeed, women often fake orgasm to facilitate their partner's orgasm and to end sex (Muehlenhard & Shippee, 2010).

The pressure to please partners and avoid feeling shame or guilt contributes to this practice, as women express a concern for their partners' satisfaction over their own sexual enjoyment (Fahs, 2011). Indeed, women who struggle with orgasm difficulties have described feeling anxiety, anger, frustration, and sadness (Lavie-Ajayi & Joffe, 2009).

Recognizing that women have received too little support in their exploration of their bodies and orgasm, sexuality educators, therapists, and researchers have developed a variety of approaches aimed at enhancing women’s sexual pleasure and orgasm. As one example, Masters and Johnson (1966) used a method of directed masturbation, which was among the first techniques that emphasized pleasure over goal or orgasm and has shown effective for certain types of sexual dysfunction (e.g., female orgasmic disorder; Both & Laan, 2008).

Madison & Meadow (1977) focused on practical sex education, conducting a one-day workshop that fostered positive changes in sexual attitudes and behaviors, including improved body and genital image, enhanced sexual functioning, and more assertive partner communication.

As another example, the Coital Alignment Technique (CAT; Eichel, de Simone, and Kule, 1988) focused on sexual positioning with a focus on clitoral stimulation, an approach that has been shown to be effective in providing consistent stimulation for female coital orgasm and treating sexual dysfunctions (Hurlbert and Apt, 1995).

Bibliotherapy has also been shown to be effective for helping women become more comfortable with their bodies, more confident in experiencing sexual pleasure, and learn to experience orgasm (Guitelman et al., 2021; Van Lankveld et al., 2021).

Betty Dodson’s Bodysex® Workshops

The 1970s were a rich period of women’s sexual empowerment, grassroots activism, and sexuality education (Bergeron, 2015). In 1973, a “dynamic Body-Sex workshop” focused on liberating masturbation was the first of its kind marketed in New York City (C. Ross, personal communication, January 29, 2024).

In 1974, Betty Dodson launched more regular events with the purpose of helping women connect with their orgasm as well as to “heal shame, enhance pleasure, and encourage self-love” (Betty Dodson & Carlin Ross Website), which Dodson came to name as Bodysex® . Ms. Dodson would first teach women about their genital anatomy and then supported them in exploring their sexual response and pathways to orgasm.

Historically, as originated by Dodson, Bodysex® workshops involved having about ten women gather in a group setting over the span of two 10-hour days to share about their experiences with orgasm and pleasure, and to participate in Bodysex® rituals, including vulva massage, Genital Show and Tell, and the Rock ‘n Roll Orgasm Technique (Betty Dodson & Carlin Ross Website).

In 2007, Carlin Ross joined Dodson and began facilitating these in-person Bodysex® workshops as well.

Dodson and Ross conducted their final joint workshop near the end of 2019. Bodysex® , however, continued to see growth as a method of promoting women’s sexual pleasure. In January 2020, Betty Dodson’s work, including Bodysex® , was featured in Gwyneth Paltrow’s “The Goop Lab” episode, titled “The Pleasure is Ours.”

Two studies have explored women’s experiences with Betty Dodson’s in-person methods; the first study explored the success rate of the “Betty Dodson method” for helping women learn to experience orgasm (Struck & Ventegodt, 2008). Among 500 anorgasmic Danish women, 93% were observed to have reached orgasm using the Dodson method (Struck & Ventegodt, 2008).

Another study utilized survey and interview methods to examine the impact of Bodysex® workshops on various aspects of women’s sexuality and relationship with their bodies (Meyers, 2015). Bodysex® participants described experiencing positive changes to their experience of orgasm, as well as improvements in their body image, sexual self-efficacy, genital acceptance and reduced genital shame/embarrassment, as well as sexual satisfaction (Meyers, 2015).

However, after some initial discussion and exploration of feasibility following the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (in April 2020), when in-person Bodysex® workshops were not possible, Ross developed a virtual one-on-one format for Bodysex® workshops.

Virtual Bodysex® workshops not only helped overcome access to orgasm education and support during a time of physical distancing recommendations related to COVID-19, but they also expanded access to a wider audience of women from around the world (C. Ross, personal communication, April 25, 2023).

However, no studies to date have explored women’s experiences with, or their orgasm-related outcomes from, participating in virtual Bodysex® workshops. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to examine women’s experiences with virtual Bodysex® , including 1) experiences with vulva massage, vaginal sensation and clitoral sensitivity, 2) characteristics of orgasm buildup and time to orgasm, and 3) the associations between masturbation and orgasm through virtual Bodysex® workshops.

METHOD

Data Collection

Data were collected as part of virtual Bodysex® workshops led by Carlin Ross, who worked in partnership with Ms. Dodson for 12 years prior to Ms. Dodson’s passing. The virtual Bodysex® workshops that are the focus of the present research included five one-on-one virtual meetings with Ross focused on orgasm, overcoming shame, and understanding the female model of sexual response.

Prior to their first session, women wrote and provided Ross with what is called a “sex essay” in the workshops. In this essay, women are asked to describe their sexual past as well as their sexual goals. After reviewing the essay, Ross would then discuss the content of the sex essay during women’s first Bodysex® session.

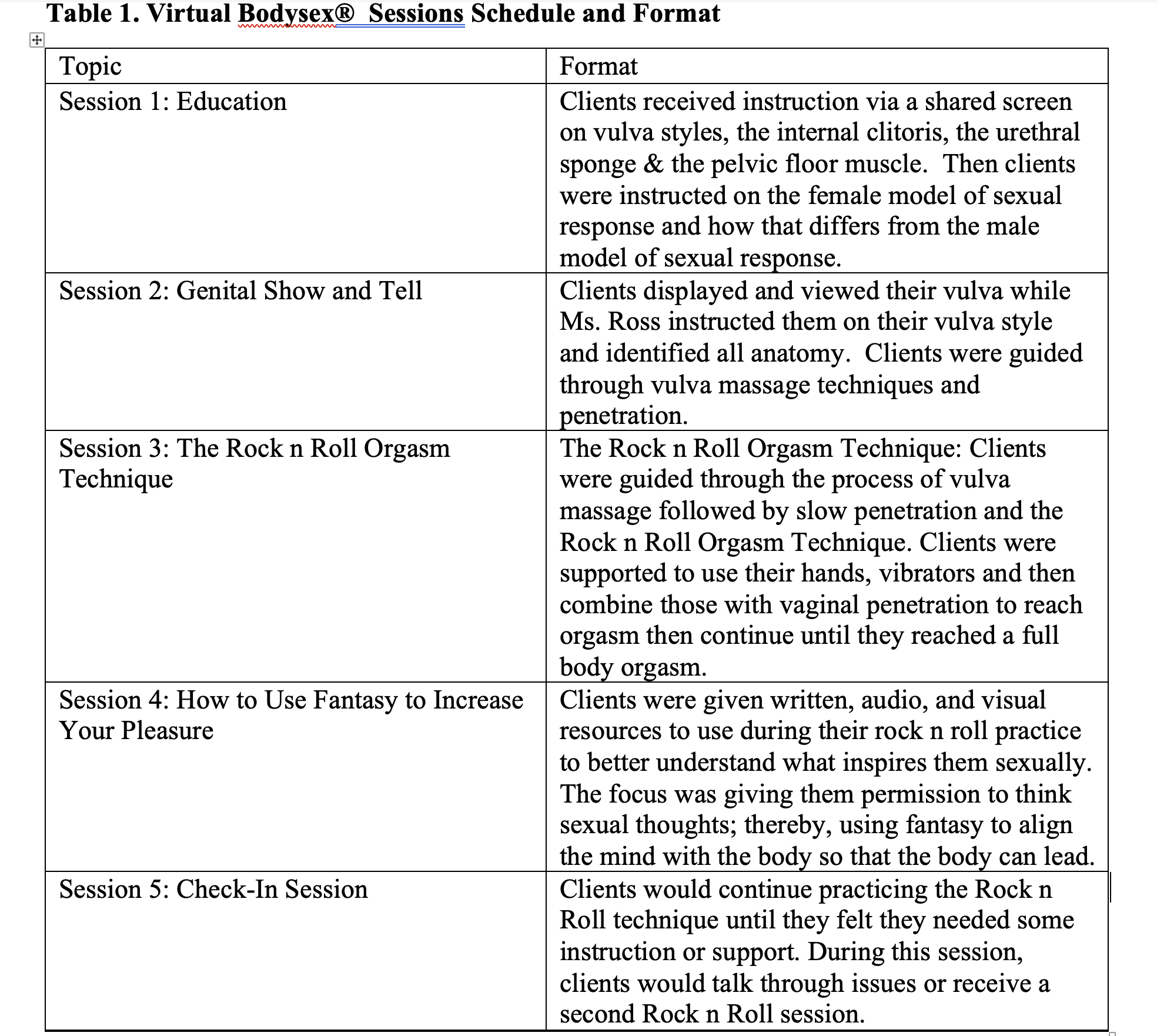

Sessions generally ran for 45-60 minutes each. These workshops were formatted to include (in this order): Education, Genital Show and Tell, The Rock ‘n Roll Orgasm Technique, How to Use Fantasy to Increase your Pleasure, and Check-In. Details about the format of each session can be found in Table 1.

The data for the present study are from virtual Bodysex® sessions that took place between April 2020 and January 2023. In early 2023, Ross emailed women who had participated in the virtual Bodysex® workshops during the aforementioned time period, provided them with a Study Information Sheet, and asked for their consent to use their de-identified data as part of a research study.

Specifically, she requested their consent to share specific notes that Ross had taken from women’s sex essays (including demographic information) as well as information she had had noted during their work together.

The latter included notes about the women’s experiences with sexuality while growing up, their experiences viewing their own vulva, masturbation history, experiences with orgasm buildup (e.g., how their body moves as it approaches orgasm), self-reported feelings of guilt and shame related to masturbation or sexuality, painful sex or penetration, vulva massage, and their time to orgasm.

Ms. Ross did not share the sex essays themselves, but rather key points from these essays. Women who consented to have their de-identified information included in the research were asked to reply directly to Ross’ email and say “I consent to have my information included in your research project.” Ross then then compiled the data from individuals who consented and placed them into a de-identified spreadsheet which was then shared with the researchers.

The Institutional Review Board at the authors’ university reviewed a description of this secondary data analyses and did not consider it to be human subjects research.

Measures

Receipt of Sex Information

In their essays, clients were asked to describe their upbringing as it related to sexuality. In these responses, clients described whether they received any information about sex growing up. These responses were recorded and analyzed dichotomously (e.g., 0 = did not receive sex information, 1 = did receive sex information).

Trauma and Shame

Information about clients’ past experiences with trauma and/or shame came from two potential sources: their sex essay and their initial Virtual Bodysex® session. In the essay, in response to the question “What was your religious upbringing; your parent's attitude towards sex?” clients sometimes shared information related to trauma and/or shame related to sex or sexuality.

Additionally, as part of their first virtual Bodysex® session, clients sometimes referenced shame or prior trauma in response to Ross asking: “Are you masturbating on a regular basis?” That is, sometimes their feelings of shame or their prior traumas were mentioned as reasons they were no longer masturbating at all or as often as before, or that memories of these traumas interfered with their masturbation experiences.

Ross recorded notes about these experiences from clients’ responses. For the purposes of the current research, these responses were dichotomized as 0 (no trauma/shame reported) and 1 (trauma/shame reported).

Masturbation

Ross documented information about clients’ childhood, teen, and adult masturbation practices that had been shared by clients through their sex essays as well as in their first virtual Bodysex® session. In the essay, clients responded to the question, “What was your first memory of masturbation?” Responses were recorded as depicting either childhood or adolescent masturbation experiences (or both childhood and teen).

Also in the essay, clients sometimes described their adult masturbation in response to the question, “What is your current sex life?” She also asked clients “Are you masturbating on a regular basis?” For each category of masturbation (childhood, teen, and adult), responses were dichotomized as yes (1) or no (0), to describe whether the participant reported having masturbated at each stage.

Baseline Orgasmic Response

No Orgasm. Prior to beginning the Bodysex® workshops, women were asked “What is your sex goal – what do you desire?” In response to this question, clients often described their desire for some type of orgasm enhancement or facilitating orgasm (e.g., I want to be able to connect to my body and create an orgasm that is fulfilling; C. Ross, personal communication, January 29, 2024), and in these responses, sometimes stated whether they had never had an orgasm or had “lost” their orgasm. For analysis, these were dichotomized as (1) never had/lost orgasm and (0) had experienced/hadn’t lost orgasm.

Small Orgasm. During the first Bodysex® session, Ms. Ross asked clients, “Are you currently masturbating on a regular basis?” In response, clients sometimes stated that they had experienced small orgasms, but had not experienced a “full release.” Ms. Ross defined small orgasms as “a quick build up and drop off with the sensation in the genitals”; she said that, in the context of these conversations, small orgasms tended to be described as being felt only in the clitoris (C. Ross, personal communication, April 25, 2023).

For analysis, having only experienced a small orgasm was coded as 1 and responses that did not note having only experienced a small orgasm were coded as 0.

Vulva Massage

At the beginning of the Genital Show and Tell session, Ross asked clients to describe their experiences with vulva massage after one week of vulva massage “homework.” Following the vulva massage that clients enacted during the third session, Ross asked clients “How was the vulva massage?” and recorded clients’ responses to this open-ended question.

Vaginal Sensation. As part of their descriptions of their experiences with vulva massage after one week of vulva massage homework, participants described the areas that felt most sensitive. Ms. Ross subsequently observed and recorded clients’ reactions to stimulation to these areas during Genital Show and Tell.

Clitoral Sensitivity

During Genital Show and Tell, Ms. Ross asked clients to show her how they like to touch their clitoris, including which strokes they liked best. Ms. Ross subsequently observed and recorded clients’ reactions to stimulation to these areas.

Orgasm Buildup

Ross recorded information about clients’ physical reactions during orgasm buildup including whether they displayed the following: 1) head back/forward (yes/no), 2) legs tensing (yes/no), 3) buttocks lifting (yes/no), 4) mouth opening (yes/no), 5) sounds (yes/no), and/or 6) shaking (yes/no). These characteristics were not exclusive. All participants were observed experiencing at least two of these.

Time to Orgasm

Ross timed and recorded the time that it took women (in minutes) to reach orgasm through Rock n Roll sessions and, when clients’ first orgasm was a small orgasm, the length of time it took for participants to achieve a full body orgasm. Ross defined full body orgasm as: “An orgasm where the energy is felt through-out the body - Tingling in the hands/face/feet, shaking of legs, etc. It's like a wave that passes over the body” (C. Ross, personal communication, April 25, 2023).

Ross also recorded the number of Rock ‘n Roll sessions that clients needed before reaching orgasm (of note, there was no additional cost if additional sessions were needed).

Analysis

SPSS 29 was used to conduct all statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were generated for demographic characteristics, no sex information while growing up, orgasm experience (no orgasm/lost orgasm as compared to small orgasm), time to orgasm and time to full body orgasm. Frequencies were also calculated for orgasm buildup characteristics and combinations of buildup characteristics based on the methods utilized in previous research (Richters et al., 2006; Herbenick et al., 2010).

Independent samples t-tests were used to examine the relationships between 1) no prior orgasm/lost orgasm and time to orgasm, 2) no prior orgasm and time to full body orgasm, and 3) time to orgasm and childhood, teen, and adult masturbation.

Inductive thematic analysis (Nowell et al., 2017) was used for responses recorded by Ms. Ross related to vulva massage, clitoral sensitivity, and vaginal sensation. CP coded responses and named themes and DH reviewed and confirmed coding. Frequencies were calculated for thematic categories.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

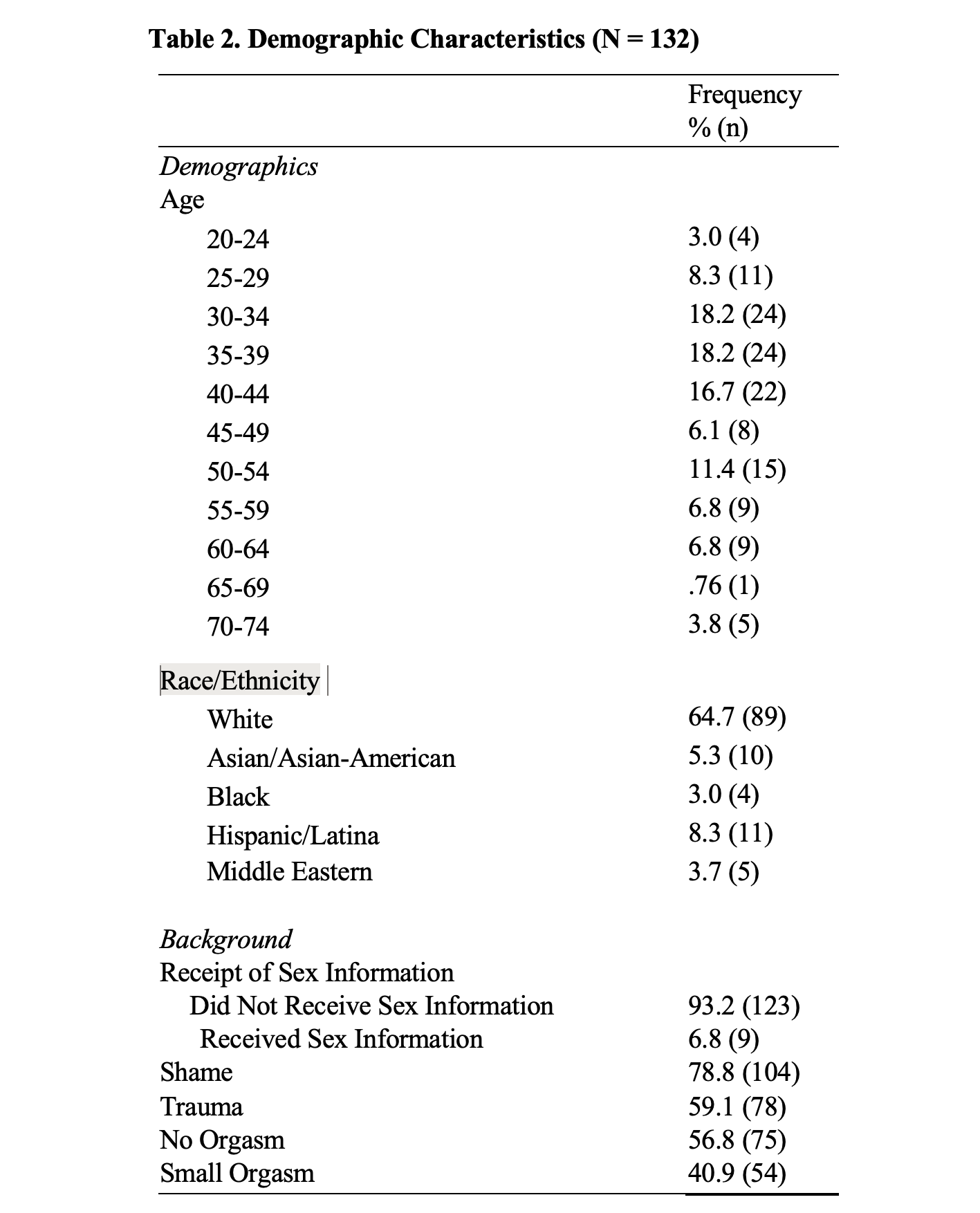

Participants were 132 women between the ages of 21 and 74 (mean = 42.42, SD = 12.17, median = 40) who had participated in one-on-one virtual Bodysex® sessions and who consented to have their data included in the present study.

These women lived in 33 countries and 23 US states. Participants were

White (n = 89, 67%),

Asian/Asian American (n = 7, 5.3%),

Black (n = 4, 3%),

Hispanic/Latina (n = 11, 8.3%), and

Middle Eastern (n = 5, 3.8%).

Thirteen participants (9.8%) identified as Jewish.

**A majority of the sample (n = 123, 93.2%) hadn’t received information about sex growing up.

**More than three-quarters of women (79%, n = 104) described shame through their sex essays or during their virtual Bodysex® session, and more than half of women (59.1%, n = 78) disclosed specific trauma or abuse (59.1%, n = 78) related to their sexuality. Demographic characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 2.

Vulva Massage

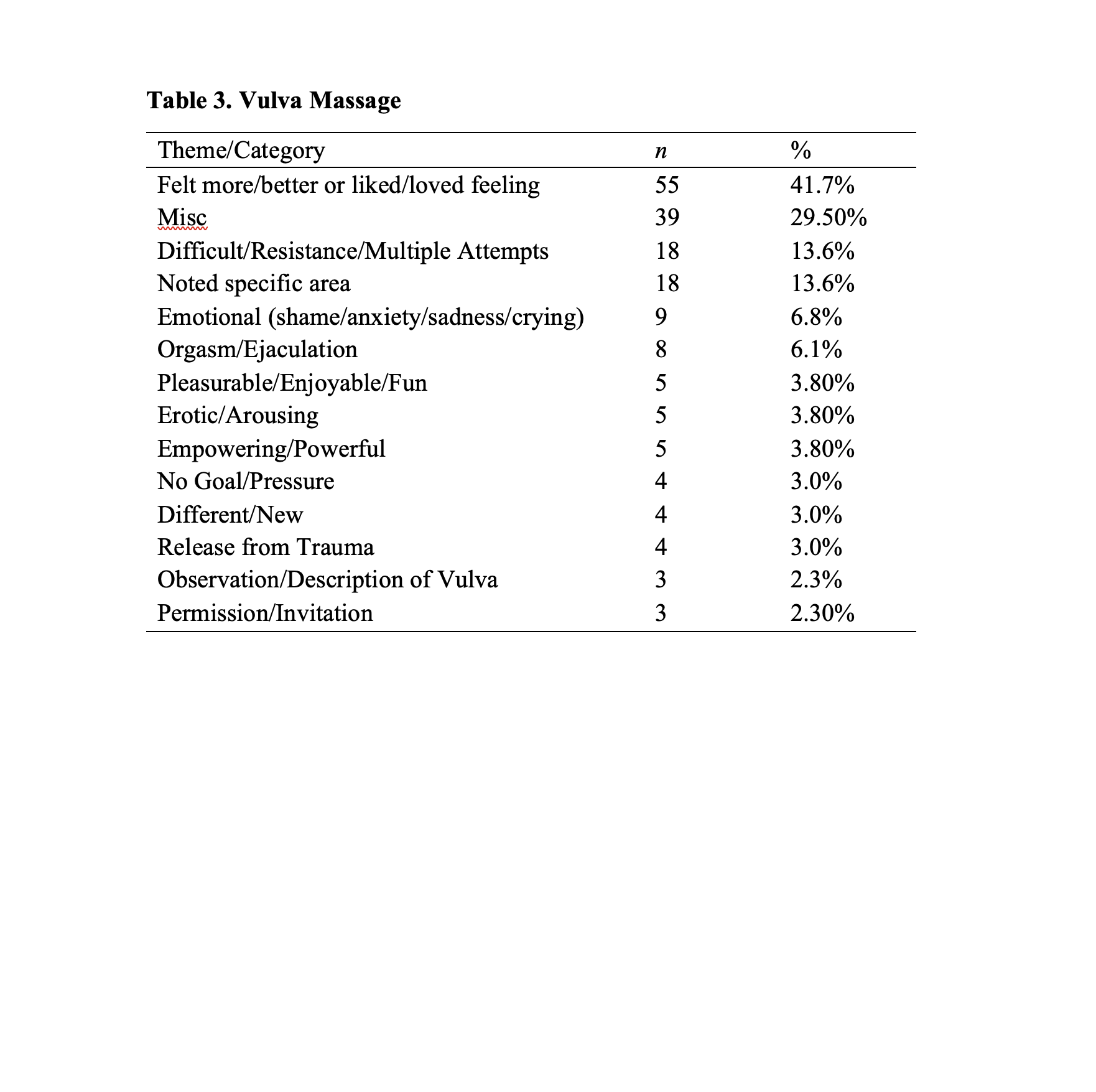

As shown in Table 3, participants most commonly (41.7%, n = 55) reported that vulva massage allowed them to feel more or better sensations or that they liked or loved the feelings associated with vulva massage.

Other common reactions included that vulva massage was difficult (13.6%, n = 8) or feeling resistance to vulva massage, often taking multiple attempts before they were able to engage in vulva massage (13.6%, n = 18).

Some participants noted a specific area that they most enjoyed touching, or that felt the best (13.6%, n = 18). Nine participants (9%) noted that the vulva massage evoked feelings of shame, anxiety, sadness, or that they cried. Eight participants (6.1%) indicated that they had experienced orgasm or ejaculation from engaging in vulva massage.

Women also described the vulva massage as feeling:

different or new (3%, n = 4),

pleasurable, enjoyable, or fun (3.8%, n = 5),

erotic/arousing (3.8%, n = 5),

powerful or empowering (3.8%, n = 5).

Several participants said the vulva massage felt like they were had been given permission or invited to love their vulva (2.3%, n = 3), that they felt a release from trauma through vulva massage (3%, n = 4), or that they enjoyed not having a goal or feeling pressured to orgasm through vulva massage (3%, n = 4).

Finally, three participants responded with an observation about or description of their vulva (e.g., that their vulva was soft or kind). Other miscellaneous responses that didn’t fall into a category included mentions of feeling in control, enjoying the use of oil for vulva massage, using breathing techniques, using “tender touch,” feeling like they were making progress, feeling numbness at first and then pleasure, describing their clitoris as feeling “invigorated,” feeling like it “gave (her) energy,” and that their vulva felt “alive.”

A full list of themes can be found in Table 3.

Clitoral Sensitivity

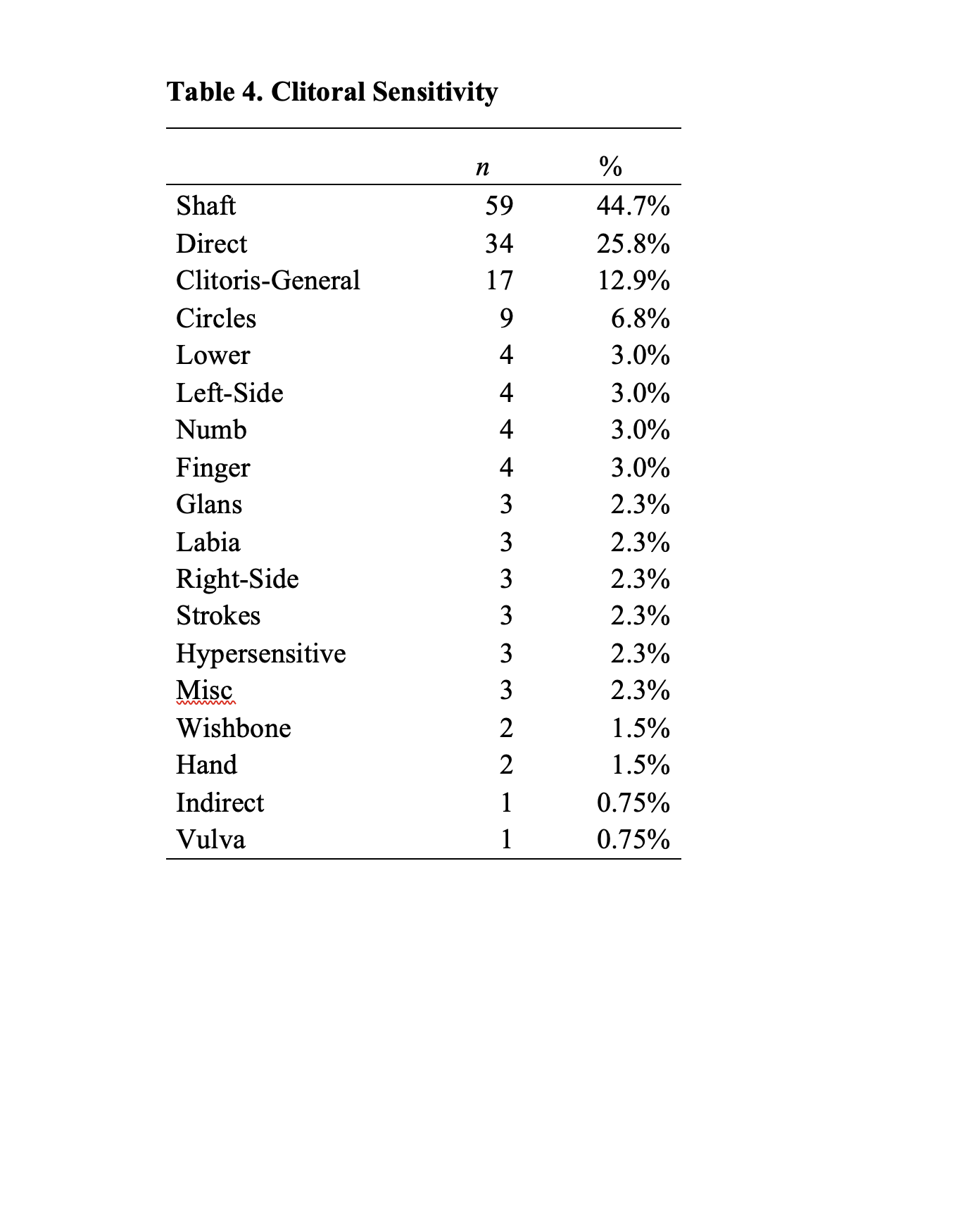

As shown in Table 4, participants most frequently experienced clitoral sensitivity when touching their clitoral shaft (n = 59, 44.7%), or clitoris more generally (n = 17, 12.9%) and most frequently reported enjoying direct stimulation (n = 34, 25.8%), followed by circular motions (n = 9, 6.8%).

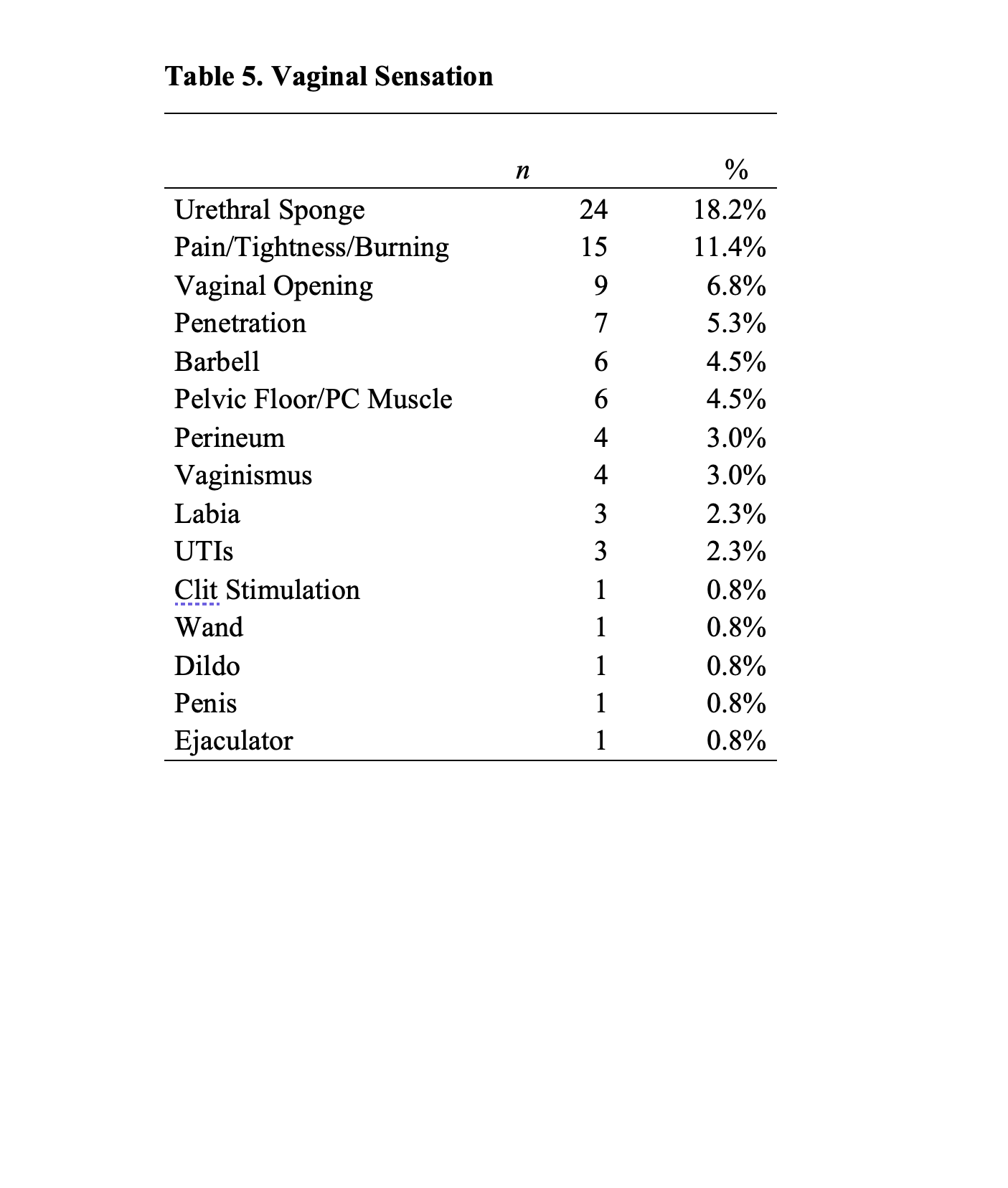

Vaginal Sensation

In their descriptions of vaginal sensations (and as shown in Table 5), participants most frequently noted experiencing that they experienced the most sensation at the urethral sponge (n = 24, 18.2%), vaginal opening (n = 9, 6.8%), perineum, (n = 4, 3%) and labia (n = 3, 2.3%). Fifteen participants reported feeling pain, tightness and/or burning sensations (11.4%) and four specifically noted vaginismus (4%).

Orgasm and Buildup

Prior to their first virtual Bodysex® session, more than half (n = 75, 56.8%) of women reported either never having had an orgasm or having “lost” their orgasm at some point, and 40.9% (n = 54) reported only having previously experienced a small orgasm. Through virtual Bodysex® sessions, most women (n = 91, 68.9%) were able to experience orgasm with one Rock ‘n Roll session, while one quarter did so with two sessions (n = 33, 25%), and 3% of women (n = 4) experienced orgasm in their third Rock ‘n Roll sessions.

Participants took between 3-32 minutes to reach orgasm (M = 12.49; SD = 6.435, median = 12) and 6-48 minutes to reach full body orgasm through Rock ‘n Roll sessions (M = 19.69, SD = 7.776, median = 18)

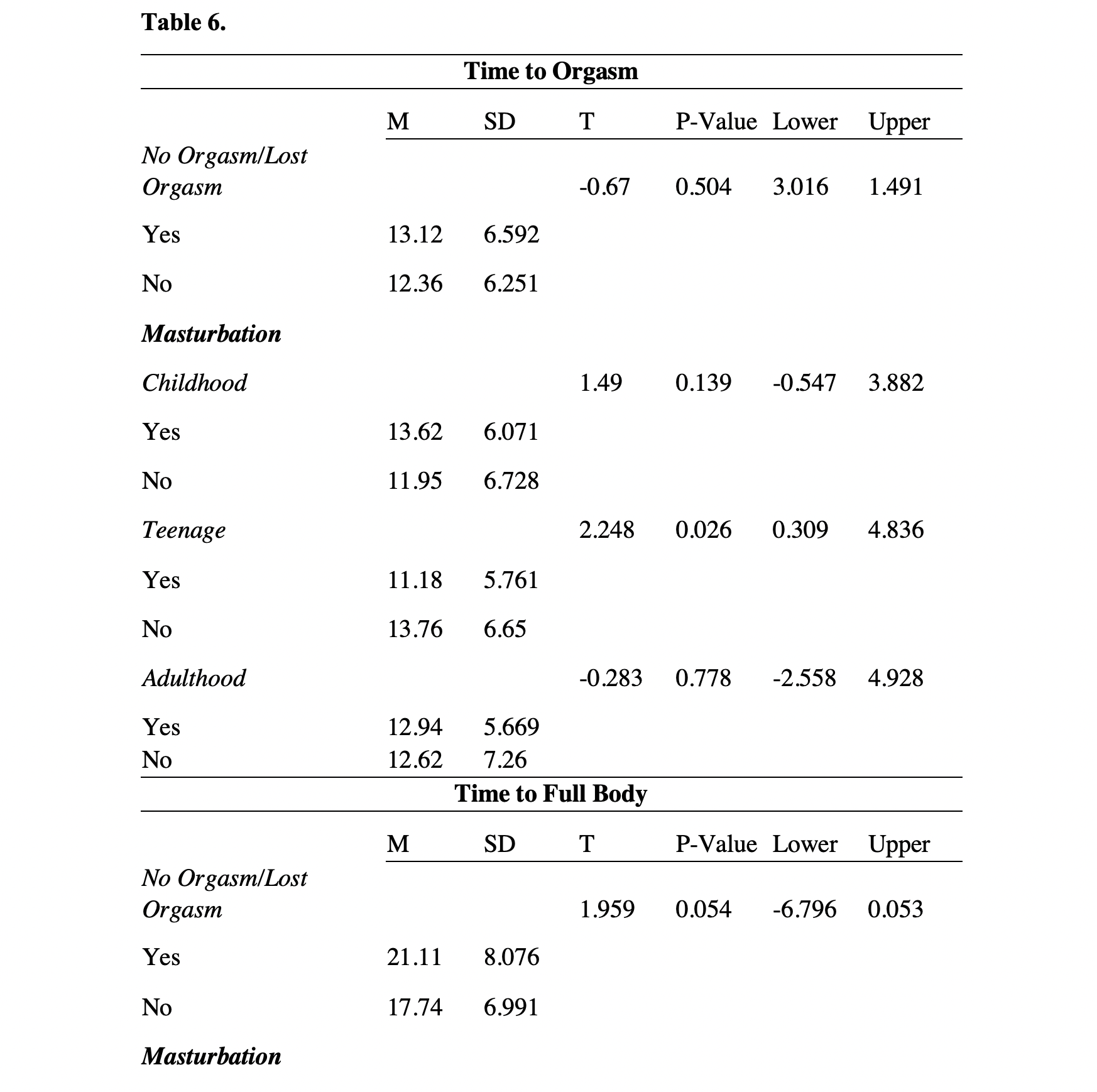

Time to orgasm and time to full body orgasm did not significantly differ among women who never previously had/lost their orgasm (time to orgasm: M = 13.12, SD = 6.592; time to full body orgasm: M = 21.11, SD = 8.076) compared to women who had experienced/had not lost orgasm (time to orgasm: M =12.36, SD = 6.251; time to full body orgasm: M = 17.74, SD = 6.991).

**Women who reported teen masturbation (M = 11.18, SD = 5.761) compared to women who did not report teen masturbation (M = 13.76, SD = 6.65) demonstrated significantly shorter time to orgasm.

**The same was observed for full body orgasm; compared to women who did not report teen masturbation (M = 21.39, SD = 8.433), women who reported teen masturbation (M = 16.80, SD = 5.517) demonstrated significantly shorter time to full body orgasm.

No significant differences in time to orgasm or full body orgasm were observed for childhood masturbation or adulthood masturbation (Table 6).

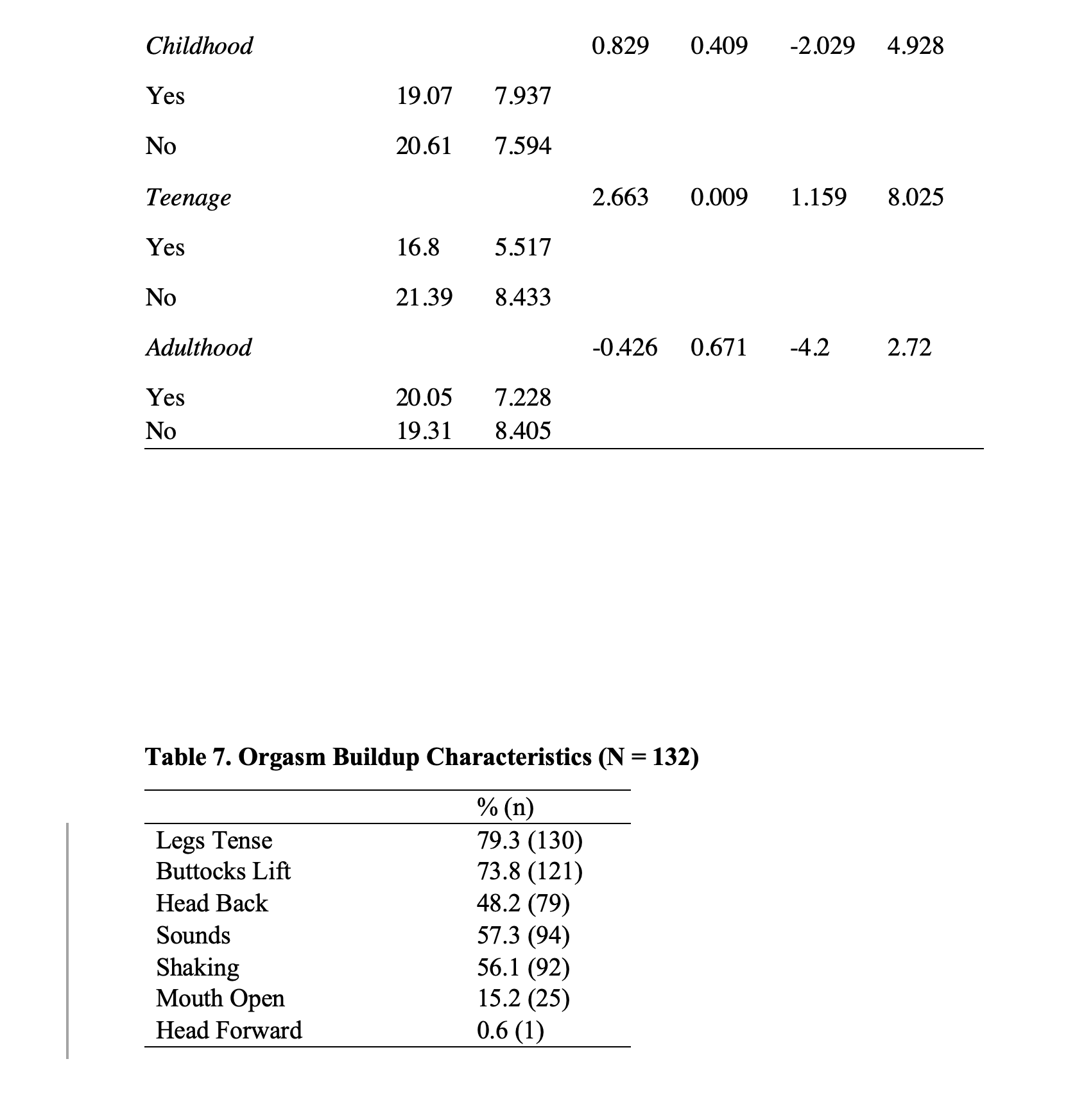

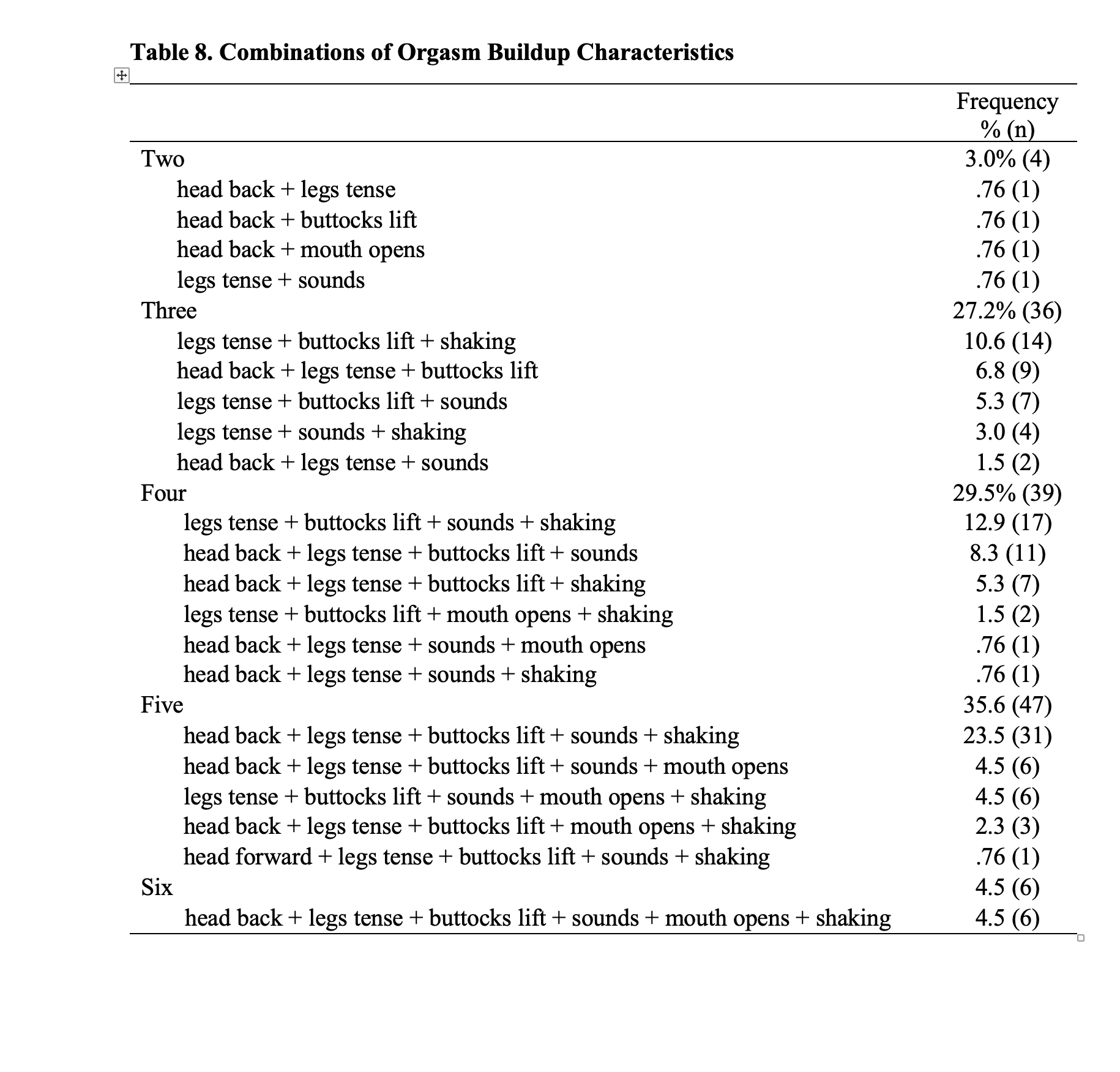

A total of 21 combinations of orgasm buildup characteristics were observed.

Legs tensing (79.3%, n = 130),

buttocks lifting (73.8%, n = 121),

sounds (57.3%, n = 94) and

shaking (56.1%, n = 92) (Table 7).

No specific combination of characteristics was observed in the majority of the sample. However, the combination of head back, legs tensing, buttocks lifting, sounds, and shaking was observed in nearly a quarter of the women (Table 8).

DISCUSSION

The current study aimed to examine the experiences of 132 women who had participated in virtual Bodysex® sessions, focusing on 1) their experiences with vulva massage, vaginal sensation and clitoral sensitivity, 2) characteristics of orgasm buildup and time to orgasm, and 3) the associations between masturbatory practices and time to orgasm through the virtual Bodysex® sessions.

Nearly all of the women who participated in virtual Bodysex® disclosed prior experiences with trauma and/or shame surrounding sexuality, sexual pleasure, and/or orgasm. This aligns with prior research that demonstrates the complex relationship that many women have with their vulvas (Braun & Wilkinson, 2001;2003; Fahs, 2014; Herbenick et al., 2011), and especially touching their vulvas for sexual exploration or pleasure, with these feelings often rooted in feelings of guilt or shame.

One goal of Bodysex® , has been described as aiming to transform the experience of orgasm, taking something that has previously been associated with shame, trauma, violence, failure, pressure, or lack of safety into an experience that feels safe, fun, supported, and/or light-hearted, and that lacks pressure (C. Ross, personal communication, January 29, 2024; Dodson, 2012; Ross & Dodson, 2017).

Mixed reactions to vulva massage depict a spectrum of women’s experiences with and feelings about exploring and/or reconnecting with their bodies. In describing their experiences with virtual Bodysex® , many women described vulva massage as an emotional experience. While some felt sadness, anxiety, or shame, others described the experience with positive adjectives (e.g., empowering, arousing, pleasurable, and fun).

Variability across women’s experiences with vulva massage may reflect the diversity in women’s experiences with trauma and shame, the point in their healing journey at which they participated in virtual Bodysex® , and/or the goals that women hope to achieve through these sessions.

In addition, several women expressed enjoying that there was no pressure or goal to orgasm through vulva massage, experiencing a release from trauma, and feeling that they were being given permission/invitation to explore. These findings may also speak to the value of permission and limited information, often highlighted in the PLISSIT model commonly used by sexuality educators, counselors, and therapists (PLISSIT; Annon, 1976).

The current study also improves our understanding of women’s experiences with orgasm as well as orgasmic variability, the latter which has received limited scholarly attention. Masters and Johnson (1966) were the first to note “variation in the female orgasmic experience” (p. 6), and several others have empirically explored orgasmic diversity (Herbenick et al., 2018; Weitkamp & Wehrli, 2023).

Our findings support and extend the extant literature by speaking to the specific variation that exists in orgasm buildup among women, considering the observed 21 combinations of orgasm buildup characteristics.

This diversity may further reinforce that the traditional theoretical models that aim to characterize sexual response may be insufficient on their own (Ferenidou et al., 2016) to describe or encompass all possible expressions or variations of sexual response that lead to orgasm among women.

All of the women in the sample were able to experience orgasm—sometimes after up to three Rock ‘n Roll sessions, but often sooner than this. Also, having lost or having never experienced orgasm was not associated with the time it took women to experience orgasm through these virtual sessions. These findings raise questions about what characteristics of the virtual workshops work for women? In her qualitative work describing women’s best orgasm experiences, Fahs (2014) noted the “power of interpersonal connection” (Fahs, 2014, p. 980).

Though her work specifically referenced feelings of closeness between sexual partners, it is possible that the power of interpersonal connection extends to the professional relationship between clients and Bodysex® practitioners, especially given the intimate space they share through the virtual sessions (which includes explicit conversation and suggestions related to self-pleasuring as well as the practitioner viewing the client’s nude body and sexual exploration).

With regard to women’s experiences with orgasm in the current study – even though Bodysex® practitioners are not sexual partners per se, they are partners in a woman’s pleasure journey. In the field of sexuality, controversies remain over sexuality professionals using touch as a method in their practice.

Being virtual, these workshops did not involve physical touch between the practitioner and participant. However, they did involve the professional being present for participants, viewing their nude body, and supporting them through their own vulvar and sexual self-exploration.

With the world presenting more opportunities related to virtual therapies as well as Artificial Intelligence (AI) guides, more research is needed to understand the diverse forms of connection and support that people might benefit from in their own sexual journeys, including both human-centered supports as well as technology-facilitated supports.

There are many ways that people explore their sexuality; sex toys, sex dolls/robots, and sexual surrogates, to name a few, are all examples of the wide range of tools/supports that make sex both possible (as is often the case for people living with certain disabilities) as well as pleasurable for many people.

Among the advantages of virtual Bodysex® workshops, at least in comparison with in-person workshops, is that they allow participants to participate from their comfort of their own home and may be more affordable, given the lack of costs associated with travel or lodging. Participants can also customize some aspects of their experience, such as through adjusting the camera positioning, lighting, or supporting positions (e.g., the use of their bed, pillows, or other supports) (C. Ross personal communication, January 29, 2024). The ability to manipulate the physical environment may appeal to women’s diverse needs related to orgasm.

That said, there are likely some disadvantages too. For example, some people may not have sufficient privacy at home in order to engage in virtual orgasm workshops. Additionally, some people may feel comfortable with the practitioner and/or the exercises but not trust the security of the technology; such anxiety or distrust may be barriers to them participating in virtual sessions in the first place or, if they are participating, may be barriers to them feeling like they can fully let go, show their body and sexual exploration on the screen, and open themselves to pleasure.

Subsequent research is needed to understand the barriers and facilitators to both virtual sessions and in-person sessions, whether Bodysex® sessions or those offered by other practitioners.

Additionally, subsequent research might empirically evaluate the effectiveness of virtual Bodysex® compared to the traditionally formatted in-person Bodysex® workshops, which involve a group of women rather than just one-on-one sessions. Also, additional research should also aim to better understand experiences with virtual sessions from the perspectives of both the participants themselves and the practitioners.

Qualitative interviews may help to elucidate how virtual Bodysex® is experienced from each person’s perspective, what it means to be a partner in someone's orgasm journey, and the conditions required for individuals to feel comfortable with the experience and to achieve their goals through virtual sessions.

Strengths and Limitations

Among our strengths is that the current study moves beyond self-report to include observation. Much of what we know about people’s experiences with sexual pleasure and orgasm is based on survey research, and a principal limitation of survey research is that it relies on self-report.

In the current study, rather than only relying on self-report, an observer described what they see, including feelings/reactions that women themselves may not remember or notice as they approach orgasm (e.g., what happens to their heads or buttocks or mouth). Another strength of the current study is that time to orgasm and full body orgasm was timed and recorded by an observer during the virtual Bodysex® session, which provides more accurate estimations of time than, for example, self-report.

Our research was also subject to several limitations. First, study data derived from client notes; they were not systematically collected for the purposes of research, limiting the ability for statistical inferences. However, given that Ms. Ross had been a Bodysex® practitioner, working to help women (re)connect with their orgasm for more than a decade, and has a series of questions that she consistently uses across clients, there was sufficient consistency in the data to support an examination of these virtual workshops, which were a unique shift in how Bodysex® sessions evolved in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic.

A second limitation pertains to possible selection bias. That is, we are unable to examine data from women who did not consent to have their deidentified data shared with our research team. Thus, it is possible that the women who consented to have their data shared for the purposes of research were different in some way than non-responders—perhaps more open to experience, for example. Alternatively, they may have had a different experience with the virtual workshops, such as feeling more or less satisfied with their experience.

Additionally, having lost and having never experienced an orgasm were recorded into one category of no orgasm, given that they were not having orgasms at the time that they began the sessions (even though those coded as “lost orgasm” had experienced orgasm at some earlier point in their lives).

Though we were able to examine time to orgasm among women who did not currently have an orgasm in place, we were unable to examine differences between those who lost and those who never had an orgasm. Future research should work to further disentangle the differences between women who have never experienced an orgasm from women who have “lost” their orgasm and the most effective methods for facilitating orgasm among these groups.

Conclusion

The expansion of Bodysex® to a virtual format created opportunity for women living around the world to access personal support as they received support related to the genital exploration, sexual pleasure, and orgasm. These data were collected during a time that women’s sexuality, sexual expression, and pleasure remain highly politicized in many places, and include women from 33 countries and 23 U.S. states.

The diverse backgrounds of women seeking out these sessions may also, in and of itself, reinforce the need for resources to support women in their sexual exploration and pleasure. That so many women were able to connect with their orgasm through virtual Bodysex® suggests that this program can be an effective option to expand access to sexual pleasure and orgasm despite geographical boundaries.

References

Annon, J.S. (1976). The PLISSIT Model: A Proposed Conceptual Scheme for the Behavioral Treatment of Sexual Problems. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 2, 1-15.

Beckmeyer, J. J., Herbenick, D., Fu, T. C., Dodge, B., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2021). Pleasure during adolescents’ most recent partnered sexual experience: Findings from a US probability survey. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(6), 2423-2434.

Bergeron, R. (2015, August 17). ‘The Seventies’: Feminism makes waves. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2015/07/22/living/the-seventies-feminism-womens-lib/index.html

Both, S., & Laan, E. (2008). Directed masturbation: A treatment of female orgasmic disorder. Cognitive behavior therapy: Applying empirically supported techniques in your practice, 158-166.

Boydell, V., Wright, K. Q., & Smith, R. D. (2021). A rapid review of sexual pleasure in first sexual experience (s). The Journal of Sex Research, 58(7), 850-862.

Braun, V., & Wilkinson, S. (2001). Socio-cultural representations of the vagina. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 19(1), 17-32.

Braun, V., & Wilkinson, S. (2003). Liability or asset? Women talk about the vagina. Psychology of Women Section Review, 5(2), 28-42.

Chadwick, S. B., & Van Anders, S. M. (2022). Orgasm Coercion: Overlaps Between Pressuring Someone to Orgasm and Sexual Coercion. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(1), 633–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02156-9

Dodson, B. (1992). Sex for one: The joy of selfloving. Three Rivers Press., Chicago,

Eichel, E. W., de Simone, J., & Kule, S. (1988). The technique of coital alignment and its relation to female orgasmic response and simultaneous orgasm. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 14(2), 129–141. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.1080/00926238808403913

Fahs, B. (2011). Performing sex: The making and unmaking of women's erotic lives. State University of New York Press.

Fahs, B. (2014). Genital panics: Constructing the vagina in women's qualitative narratives about pubic hair, menstrual sex, and vaginal self-image. Body Image, 11(3), 210-218.

Fahs, B. (2014). Coming to power: Women's fake orgasms and best orgasm experiences illuminate the failures of (hetero) sex and the pleasures of connection. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 16(8), 974-988.

Fahs, B., & Plante, R. (2017). On ‘good sex’and other dangerous ideas: Women narrate their joyous and happy sexual encounters. Journal of Gender Studies, 26(1), 33-44.

Ferenidou, F., Kirana, P. S., Fokas, K., Hatzichristou, D., & Athanasiadis, L. (2016). Sexual Response Models: Toward a More Flexible Pattern of Women's Sexuality. The journal of sexual medicine, 13(9), 1369–1376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.07.008

Gavey, N., McPhillips, K., & Braun, V. (1999). Interruptus Coitus: Heterosexuals Accounting for Intercourse. Sexualities, 2(1), 35–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346099002001003

Guitelman, J., Mahar, E. A., Mintz, L. B., & Dodd, H. E. (2021). Effectiveness of a bibliotherapy intervention for young adult women’s sexual functioning. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 36(2–3), 198–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2019.1660761

Herbenick, D., Barnhart, K., Beavers, K., & Fortenberry, D. (2018). Orgasm range and variability in humans: A content analysis. International Journal of Sexual Health, 30(2), 195-209.

Herbenick, D., Fu, T. C., Arter, J., Sanders, S. A., & Dodge, B. (2018a). Women's experiences with genital touching, sexual pleasure, and orgasm: results from a US probability sample of women ages 18 to 94. Journal of sex & marital therapy, 44(2), 201-212.

Herbenick, D., Barnhart, K., Beavers, K., & Fortenberry, D. (2018b). Orgasm range and variability in humans: A content analysis. International Journal of Sexual Health, 30(2), 195-209.

Herbenick, D., Reece, M., Schick, V., Sanders, S. A., Dodge, B., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2010). An event-level analysis of the sexual characteristics and composition among adults ages 18 to 59: results from a national probability sample in the United States. The journal of sexual medicine, 7 Suppl 5, 346–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02020.x

Herbenick, D., Schick, V., Reece, M., Sanders, S., Dodge, B., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2011). The Female Genital Self-Image Scale (FGSIS): Results from a nationally representative probability sample of women in the United States. The journal of sexual medicine, 8(1), 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02071.x

Hurlbert, D. F., & Apt, C. (1995). The coital alignment technique and directed masturbation: a comparative study on female orgasm. Journal of sex & marital therapy, 21(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926239508405968

Klein, V., Laan, E., Brunner, F., & Briken, P. (2022). Sexual pleasure matters (especially for women)—Data from the German sexuality and health survey (GeSiD). Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 19(4), 1879-1887.

Lavie-Ajayi, M., & Joffe, H. (2009). Social Representations of Female Orgasm. Journal of Health Psychology, 14(1), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105308097950

Madison, J., & Meadow, R. (1977). A one-day intensive sexuality workshop for women. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 3(1), 38-41.

Mahar, E. A., Mintz, L. B., & Akers, B. M. (2020). Orgasm equality: Scientific findings and societal implications. Current Sexual Health Reports, 12(1), 24-32.

Masters, W.H., & Johnson, V. E. (1966). Human sexual response. Little, Brown.

McCary, J. L., & Flake, M. H. (1971). The role of bibliotherapy and sex education in counseling for sexual problems. Professional Psychology, 2(4), 353–355. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0021398

Meyers, L. (2015). Answering the call for more research on sexual pleasure: A mixed method case study of the Betty Dodson Bodysex® workshops. Pennsylvania: Widener University.

Moura, C. V., Tavares, I. M., & Nobre, P. J. (2020). Cognitive-affective factors and female orgasm: a comparative study on women with and without orgasm difficulties. The journal of sexual medicine, 17(11), 2220-2228.

Muehlenhard, C. L., & Shippee, S. K. (2010). Men's and women's reports of pretending orgasm. Journal of sex research, 47(6), 552-567.

Potts, A. (2000). Coming, Coming, Gone: A Feminist Deconstruction of Heterosexual Orgasm. Sexualities, 3(1), 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346000003001003

Richters, J., De Visser, R., Rissel, C., & Smith, A. (2006). Sexual practices at last heterosexual encounter and occurrence of orgasm in a national survey. Journal of sex research, 43(3), 217-226.

Ross, C., & Dodson, B. (2017). Betty Dodson Bodysex Basics. Betty A Dodson Foundation Inc.

Struck, P., & Ventegodt, S. (2008). Clinical holistic medicine: teaching orgasm for females with chronic anorgasmia using the Betty Dodson method. TheScientificWorldJournal, 8, 883–895. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2008.116

Thouin-Savard, M. I. (2019). Erotic mindfulness: A core educational and therapeutic strategy in somatic sexology practices. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 38(1), 14.

Van Lankveld, J. J. D. M., Van De Wetering, F. T., Wylie, K., & Scholten, R. J. P. M. (2021). Bibliotherapy for Sexual Dysfunctions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 18(3), 582–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.12.009

Acknowledgments

Callie Patterson1,2

Debby Herbenick1,3

Shahzarin Khan1,3

1 Center for Sexual Health Promotion, Indiana University School of Public Health, Indiana University. Bloomington, IN. United States.

2 Department of Public Health, Des Moines University, West Des Moines, IA. United States.

3 Department of Applied Health Science, Indiana University School of Public Health, Indiana University. Bloomington, IN. United States.

Funding Information: Betty Dodson Foundation

Corresponding author:

Callie Patterson Perry, PhD

Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health

Des Moines University

West Des Moines, IA 50266