The Language of the Goddess

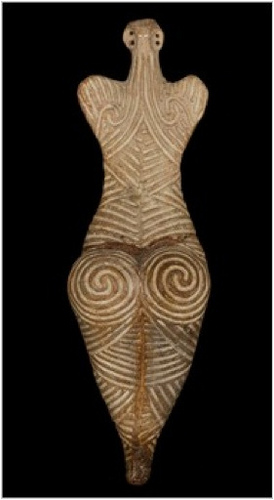

Noting that you’ve been celebrating Marija Gimbutas reminds me how important she is when I talk to my students about her work in creating the language of the goddess (also the title of one of her most fascinating books).

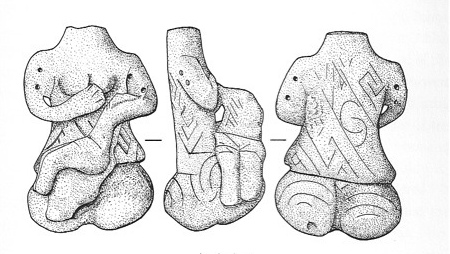

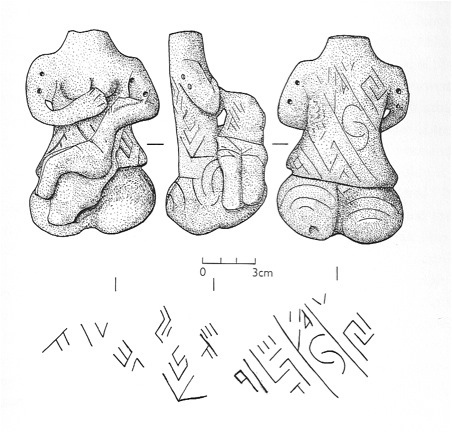

Cucuteni figurine, 4050-3900 B.C.

Gimbutas, a Lithuanian-American archeologist, spent her career excavating both Neolithic and Bronze Age sites in what she labeled “Old Europe” — areas like modern day Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldavia, parts of Greece, Sardinia and so on.

Gimbutas’ Language of the Goddess

What made her approach somewhat unusual was that she fused archeology with linguistics and myth and is largely responsible for pioneering something called archeo-mythology. Her focus was principally on the period beginning with early agriculture — a period dominated by what she described as goddess-worshipping, earth-centered, non-violent, and egalitarian. Male deities often appear as the partners of goddesses.

To Gimbutas, the parthenogenic — that is, “self-fertilizing” goddess — the goddess who reproduces without a male partner — was the most persistent symbol in the archeological record of the ancient world. She spent her career devoted to decoding symbols and signs on pottery, figures, tools, tombs and other decorated objects.

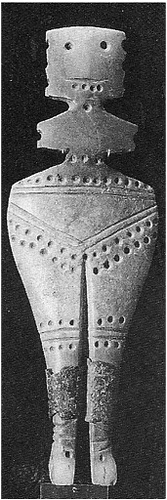

7000 Year-Old Couple (Gumelnita lovers)

Gimbutas supports her theory of this early social order by pointing to the striking absence of images of warfare and male domination. The presence, for example, of priestesses or women as heads of their clans — societies in Minoan Crete and Malta being a couple of examples — reflected, in her opinion, a much more balanced system. Male deities appear as partners of goddesses. She describes these societies as “gylanic” — a word fusing the Greek word for woman “gyn” and the Greek word for man, “andros.”

Symbols

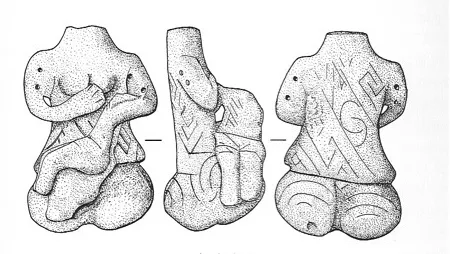

Gimbutas tracks repeated female symbols in art and architecture and comes up with a kind of pictorial script of recurring images. Symbols and images invariably cluster around fertility and regeneration. The art of these agrarian village cultures is manifested by signs of dynamic motion — whirling spirals, winding and coiling snakes, circles, crescents, horns, sprouting seeds and shoot, birds and frogs.

Vulvas in Cave Art

According to Gimbutas, signs like the V symbol or chevron were prevalent motifs since the Paleolithic period — and among the earliest symbols denoting what she believed to be hieroglyphics of the life-giving goddess. Graphically, the pubic triangle is most directly rendered as a V — and is thus in her opinion a universally recognized one.

Reindeer Bone with Chevrons

These pre-Neolithic fragments of reindeer-antler tools decorated with chevrons from France, for instance, suggest this early encoding of the generative symbol — a process that she traces back thousands of years.

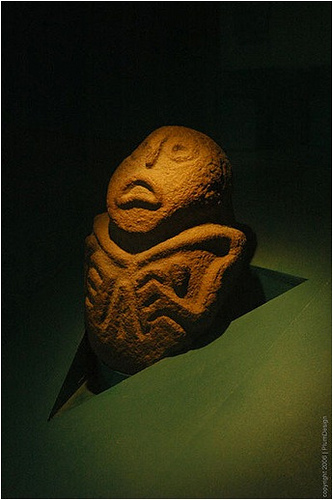

Gimbutas held that the most enduring beliefs for these agrarian cultures had to do with fertility, the fragility of life and the regenerative process. As a result, these beliefs were repeatedly manifested in anthropomorphic figures like fish, frogs, birds, and snakes.

Fish Goddess

The Fish Goddess, for example, was the presiding deity at a place called Lepenski Vir (now in present day Serbia). These figures were carved from river boulders and found at the head of altars of triangular shrines. This type of sculpture has breasts and is marked with a vulva in front. Remnants of ochre were found painted on the back of this particular piece and would suggest some sort of ritual use or purpose.

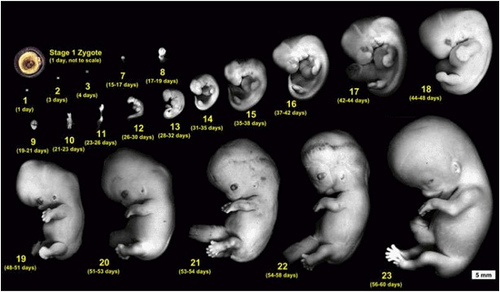

Human Gestation

Neolithic art features myriad female and frog hybrids and Gimbutas interprets them, again, as symbolic of the life force not only because of the annual spring appearance of the frog and toad but also because of the close resemblance to the human fetus — an image she feels was understood by people who celebrated the regenerative process.