I was About to Become a Porn Star When I Posed for Mapplethorpe

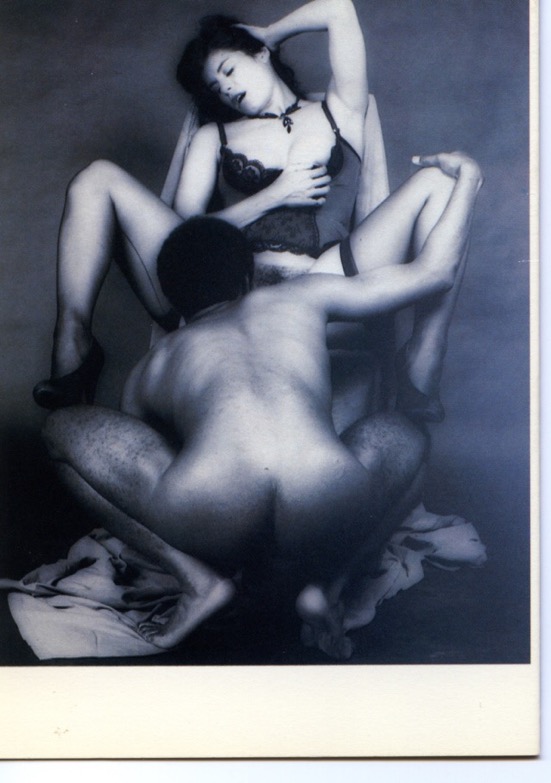

One picture is worth a thousand words, but some are worth many thousand and sometimes thousands of dollars. This story is of such a picture, a photograph by the artist Robert Mapplethorpe. When you look, you will see me, the model. What you cannot see is the story behind the image, its provenance.

On the night I met Robert Mapplethorpe he presented a slide show of black male nudes in a men’s center located in the basement of a West Village Church. It seems incongruous in light of how renowned an artist he has become to think of him in such lowly surroundings. Next week, I will travel to Los Angeles to celebrate at both the Getty Museum and the L.A. County Museum of Art, major exhibitions of Robert Mapplethorpe’s work.

I was about to become a porn star, but in 1982 that had not yet happened. I had just begun explorations into human sexuality, the field that would become my life’s work. A better description would have been swinging bachelorette, uninhibited playgirl, Catholic school survivor. I was spreading my sexual favors around the town like jam on toast, blazing a trail from Studio 54 disco to the swing club Plato’s Retreat. Sex was my preoccupation not my profession. My professional life, thus far, had been in the world of high finance.

And I had a neat little nest egg when I began to dabble in the world of erotic art. My adventures were helped along by a new circle of friends: the porn star Annie Sprinkle, tattooist Spider Webb…photographer Charles Gatewood. I began to write stories for Penthouse Variations edited by another friend, V.K. McCarty. I enjoyed writing about sex, but I was still uncomfortable with most of the visuals. The “split beavers” winking from glossy centerfolds, the graphic and gritty newsprint pages of SCREW were a shock, not a turn-on. It hurt to look at them. More than I wanted to see – I wanted to make – beautiful images of sex.

That need for a connection to my own body is what made me snap up the copy of the Village Voice that had a nude black man prominently and beautifully displayed on its cover. In the centerfold were more photos of this man, named Ajito. I saw skin, smooth and taut, stretched over muscle and bone, a human sculpture bending, bowing, testifying to his own magnificence. In my mind, I heard church bells ring. “Who has treated the body with such reverence?” The photographer was Robert Mapplethorpe. His star was just beginning to rise. I identified with Mapplethorpe’s intense curiosity, his capacity to turn bodies into unapologetic sensual objects. I knew this man could take beautiful pictures of sex and I knew I wanted to be in them. The person to whom I most wanted to expose myself was me.

Not long after, a tiny classified notice appeared, again in the Voice: “Robert Mapplethorpe will present a slide show of his ‘Black Male Nudes’…” The show would take place in a gay men’s center in the Village. It seemed like a good opportunity to meet the artist, so I called my friend Denis Florio. Denis, in his 30’s was an art world entrepreneur. He’d been dubbed “the picture framer to the stars” when the National Enquirer wrote about a consultation he’d had with Jackie O. Denis had framed everyone who was anyone in modern art: Andy Warhol, Cindy Sherman, Sandy Skoglund, Tom Wesselman. Diane Keaton visited him regularly for advice. Alice Neel painted his portrait. Chase Manhattan entrusted their collection to him. Denis, who had accrued a great eye and a stellar reputation, also appreciated the aesthetics of an uncut penis, which I told him could be abundant in the slide show presentation. Ten years earlier Denis had come to New York, a hopeful young dancer, and hung out at the legendary Max’s Kansas City along with Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith. I suggested we go to the show. “I’ll introduce you to Robert, ” he said. Perfect.

I made sure to dress for the occasion, a turquoise silk dress with a feather print. The goal was womanly and glamorous in an Ava Gardner sort of way. I was out to seduce, to inspire, to have my way with the artist, but subtly, so he would think it was all his idea.

Besides me and Denis there was just a handful of men in the church auditorium watching as Robert Mapplethorpe presented his work. Some may have been art lovers, others prospective models, some were definitely cruising. All of us were horny, needy, in some way. Afterward, Denis, Robert and I relaxed at the Pink Tea Cup Cafe, then Robert invited us back to his apartment at 77 Bleecker. The furnishings were minimalist- lots of clean lines, lots of black walls and plenty of crucifixes. I could tell by the religious content, he was my kind of guy. “And here is a sample of my work,” I said. I had not had needed to dress like a sexpot, because my offering spoke for itself. It was a magazine entitled Post Art Art in America made by me and Annie Sprinkle with our mentor, the Dutch Fluxus artist Willem De Ridder. Willem encouraged me and Annie to think of everything we did as art, so it was a sexy art magazine or an arty sex magazine, depending on how you looked at it. In one article I described the Catholic influence in my life. Another was illustrated with a photo of me wearing a corset and thigh high leather boots, while strung up in the California backyard of my friend Mistress Antoinette. The title asked, “Is There An Academy For My Kind Of Art.”

“Would you model for me, sometime?” Robert asked. Would I! It took a few months before Robert telephoned and said, “I’m photographing a black man and he would like to do some sex shots with a woman, would you…ah…be…ah…interested? He sounded so timid, almost as if he was afraid I might think he was pimping me.

“I can pay you, ” he added, “though I can’t pay much, or I could give you prints.” What would he offer me, I thought, fifty bucks? I knew I would much rather have the prints. And good little Catholic that I was, I felt much better fucking for art than for cash.

My partner’s name was Marty. I immediately conjured politically incorrect fantasies… Marty as the huge Mandingo glistening with sweat at he plundered the depths of the lily white virgin (me). The real Marty was small, but he was big where it counts. His cock was exquisitely shaped and his body definitely up to Mapplethorpian standards. Instead of the primitive cave man I imagined, he was a young corporal home on leave. He’d been reared by his religious mom to be god-fearing, proper and polite. He wore a cowboy shirt and pressed jeans. But not for long. This was actually Marty’s second modelling experience. He’d already posed for a gay magazine. That made him “A professional,” as he announced. He said the word several times, each time with a crisp, military ring. He liked the sound of it. In no time at all, corporal Marty was at attention.

It was like playing doctor. Me, Marty, Robert and Robert’s lover Jack. Jack was the photo assistant who jumped in to remove a curl from my eyes. Such sweet, gentle, fun. Robert under the dark veil of the camera, a peeping Tom who peered through the keyhole and interpreted what he saw. I was a creature under the microscope. Robert scrutinized, Jack primped, Marty fingered and stroked. I loved the attention.

We were all pretty inexperienced as pornographers. I had never had sex on camera. Robert had never photographed a man and a woman in the act. Even Marty, with his claims to “professionalism” had appeared only solo. So we were blissfully ignorant of formula poses. We did whatever popped into our heads. Mindful of Robert’s penchant for dissecting the body, I asked him to be sure one photograph showed my face.

I brought home the prints he gave me and propped them against the wall to make a closer inspection. They seemed to be three dimensional. Marty and I came alive, little creatures in a sex dance on my glass dinner table. That is when I understood what it meant to paint with light.

Some months later, a second modelling session was inspired by my romance with Officer Benson a visiting policeman with an attractive buttocks. “Hello, Robert. My lover is a policeman with a butt that deserves to be immortalized.”

Once again, I visited Robert to pick out a print. There was no image of Officer Benson’s butt, however there was a lovely one of mine and I choose it over the vulva shot. It would be much easier to hang on the wall, less intimidating to prospective dates. Why, I could even leave it up when my Dad came to visit, an anonymous buttocks and foot…who could tell?

The photos from this second session were very different from those of the first. They were much lighter, more like drawings. “I have a surprise for you,” said Robert. He presented me with my portrait, a profile from the shoulders up, taken during the shoot, but when I was unaware, an unseen Officer Benson lies beneath me. I stared at my eyes, my nose, my mouth and felt more naked in this portrait than in any photo Robert took of my genitals. I saw myself not just as a woman, but as a girl. This was not simply Veronica, this was me, Mary, having sex. “Thank you, Robert.” Little did I know how meaningful that gift would become.

From the moment of their creation, the photos took on lives of their own, like children they were off on their own adventures. Every show of Robert’s work was accompanied by excitement and controversy. An exhibition of the artist’s work was held in the city that Officer Benson called home, so arrangements were made for him to pick up his print at the gallery. He showed up in full police uniform and strode purposefully past the tulips and calla lilies to inquire where the sex photos were displayed. The nervous gallery assistant directed him to the back room, in fear that he had come to bust the show. Instead she found out that the cop was a collaborator.

In 1988 AIDS took my friend Denis Florio “picture framer to the stars. It also took Robert Mapplethorpe. A show of Mapplethorpe’s work was presented at the Whitney Museum in summer, 1989.(?) “Marty and Veronica” hung in the show and for this I was so proud–to have accomplished what I set out to do those years before, to take sex from the pages of the porn mags and class up its image, be a sort of spin doctor of sex, take it from Times Square where it was hidden, to the art museum where it could be examined and appreciated in full view.

An article by the art critic Hilton Kramer, now deceased, appeared in the New York Times on July 2, 1989. It was entitled “Is Art Above The Laws Of Decency?” In his article Hilton Kramer completely negated the idea of an artist’s “intention” as a criterion for art. For him it seemed to be all about following the accepted rules of art. Dead art. A woman possessed, I immediately sat down to write. My letter appeared in the Times under the heading “Unique Perspective.”

“By putting these images on paper, Robert accepted them as a valid part of his evolution as a human being. I think it took courage to do that. Mr. Kramer may choose to see these photos as pornography, I see them as debunking the whole idea of pornography-helping society to get rid of that self-hating concept which ghettoizes sex, which implies that some parts of our sexuality are too unspeakable to mention, too private to be public- and this is all part of some law that decent people do not question..”.

Hilton Kramer had written “What we are being asked to support and embrace in the name of art is an attitude toward life.” I countered “What we are being asked to support and embrace in the name of life is an attitude toward art. Is there any difference?”

The recognition of Robert’s vision, his skill and talent combined with so much controversy and publicity made prices soar. I decided to try to sell some of my prints. I knew very little about dealing art, but I knew a great art dealer. My friend Patrick Roger Binet of Galerie Coligny in Paris was an expert in 19th Century French drawings, not exactly modern photography, but I figured a dealer knows how to deal. He was coming to town for “Works On Paper” show of 1989 (?). One evening I met him at the show. Again, I dressed for the occasion in a high necked black lace blouse, a skirt puffy with crinolines and my waist squeezed tight in a lace-up corset. We prowled the stalls until we saw some Mapplethorpe flowers prominently displayed at the Weston Gallery booth. There were two photographs and one had sold for $18,000, that also caught our attention. I let Patrick do all the talking. He chatted up the dealers Maggie Weston and Russ Anderson, introducing me as the model, letting them know the photographs came directly to me from the artist. “Every dealer loves a great story,” said Patrick. The dealers Russ, Maggie and Maggie’s son Matt Weston were eager to come to my apartment and take a look at the prints. Russ said the photographs could sell anywhere from $8000 up. Again, I heard bells, but this time it was the tingle of the cash register. We made an appointment with them for the very next morning.

On our way downtown that night, Patrick ordered the taxi driver to halt. Leaving me in the cab, he dashed into a brand new open-all-night Korean deli and bought up every red tulip in the place. “It’s important for the dealer to treat you like a rich person, someone who is not impressed with a little money, that way he will likely offer you more. One look around your studio apartment and he might guess that you are not rich, so we must make him think you are eccentric, that way he cannot be sure.” Before we went to sleep, we filled all of the vases with tulips and when we ran out of vases we filled the pots and pans. Two dozen red tulips sat in a spaghetti pot on my Chinese red dresser next to a benevolent Balinese goddess.

As we scurried about, my dear friend and house guest porn star Gloria Leonard snoozed on the pull-out sofa. We surrounded her with so many flowers, I thought she might wake up and think she was dead. Sure enough, in the a.m. she said all that was missing was the big horseshoe that said “Good-by Guido.”

Maybe it was the flowers, in any case, the dealers wasted no time dickering about the price: 10,000, 12,000, 18,000, 20,000. My retail value seemed to be worth its weight in tulips, the kind by Mapplethorpe. He loved the erotic content of the photos and did not talk it down like it was a liability. “Don’t sell them all,” advised Maggie Weston, “Keep your portrait.”

“If you want to sell your portrait, let me know, said Russ, “I think I would like it for my private collection. Patrick’s hand shot up in the air as if he were at auction. “Me first. If anyone is going to get that portrait, I am.”

Already there was a bidding war going on. Now I really felt like a rich girl. Gloria who is as famous for what comes out of her mouth as for what went into it, had the last word. “Veronica,” she said, “you give new meaning to the phrase, ‘some day my prints will come.”

Two of the smaller prints from “Marty & Veronica” went off to the Weston Gallery, a few years later, my buttocks followed. In 1999, the large photo of “Marty and Veronica”, the one that shows my face, sold at Christie’s. I hated to part with that one, but I told myself I was not in a position to be an art collector.

Though I no longer owned the physical images, they endured in my writing and other work. I had included them in my video docu-diary “Portrait of A Sexual Evolutionary” which was the center of a censorship controversy at the University of Michigan Law School in 1993. Another connection to Robert Mapplethorpe was my friendship with Thomas Williams, the model in some of the most famous images. When Thomas and I became lovers, I felt that Robert had sent me another gift, the big, strong, black man I had imagined I would meet at that first shoot. Maybe he was still taking pictures.

As to my portrait, Patrick and I made a deal to co-own it and he took it home to Paris. Though Patrick was gay, we had started off as lovers in the late 70’s, long before A.I.D.S. was in the public consciousness. I had lived with him for a short time in Paris. Our friendship continued when he visited New York once or twice a year on gallery business. Then Patrick, too, got very sick with A.I.D.S. and I was not able to go to Paris to see him. I made lots of rationalizations as to why – reminding myself of times we had argued – but these were just feeble attempts to assuage my guilt. Patrick died in 2007.

I wondered what had happened to the portrait but I could not bring myself to ask anyone who might know. Perhaps, it had gone to pay bills as he lay ill, perhaps some other of his art dealer friends took possession of it. So be it, I thought.

This past September, I received a phone call from a couple visiting from Mexico, who invited me to dinner. I had met Eric and Francoise LeDoux in Paris where they had lived for many years. They were Patrick’s chosen family. Their son Adrien was Patrick’s godson. I welcomed the opportunity to discover what it had been like for Patrick in those last years. Was he surrounded by friends? Did he have support?

He had friends and support but it was Adrien who was steadfast – when Patrick was able taking him by wheelchair to the Louvre or to Patrick’s beloved Musee D’Orsay where he was known to be erudite. I was so grateful to know he had received such love and care.The LeDoux’s and I reminisced in the restaurant. It was a balmy night, so we moved to the sidewalk café for our coffee. “You know,” said Eric, “there is this photograph…”

“You mean the one by Robert Mapplethorpe?” I immediately unburdened myself, telling Eric and Francoise how sorry I have been not to have visited Patrick to say good-by. For years the portrait had remained over Patrick’s bed. Since his death, it had been in Adrien’s possession. It felt so good to know that though I had not made it to Paris, my portrait still had a place of honor in Patrick’s home. This news helped me to forgive myself. Not to do so would have dishonored the love of a cherished friend.

“So what do you say, you and Adrien sell the portrait and split the money?” Eric suggested. That felt so simple and so very right.

I’ve lived long enough to believe in magic and in messages from the beyond. The “lost Mapplethorpe” has now been found and at “The Perfect Moment.” It began its life as a gift from Robert Mapplethorpe, a way to say “thank you” for a collaboration. That significance has not been lost on me. What must never be lost is the spirit of self-determination that makes each of us defy rules that don’t seem to fit, to find a personal truth, and turn life into art. Whatever money comes from the sale of the original photograph will never exceed the value of its provenance. This rich history – the lives, creativity and experiences – are my treasures to share.

Read Veronica's blog