Hermaphrodites and Cross-Dressing Saints

To our Western way of thinking of gender, we seem to embrace a two-party system.

Many cultures around the world leave room for more diversity and in some cases make room for a third gender — even a fourth. The Greeks and Romans were not only comfortable but also fascinated by the duality presented by the hermaphrodite.

This famous statue of a sleeping hermaphrodite was found in Pompeii, one of two Roman towns destroyed in 79 AD by a volcanic eruption. It was not rediscovered for some 1800 years.

The ancient Greeks were among the first to incorporate this theme into a myth — the story of Hermaphroditus.

Hermaphroditus was the son of the goddess of love — Aphrodite (Venus as the Romans called her) — and Hermes, the messenger of the gods.

One day, Hermaphroditus was minding his own business when the nymph Salmacis approached him and wanted to seduce him on the spot. Our hero, however, was not interested and declined her offer. When he thought she was gone, Hemaphroditus proceeded to take a dip in her empty pool. Suddenly Salmacis reappeared and decided she was going to have her way with him no matter what.

He tried resisting but Salmacis requested help from the gods to keep them together — and well, her wish was granted. The two of them fused into a single body with both male and female sexual characteristics. Hence, we have the term hermaphrodite — a term that defines a person of both sexes.

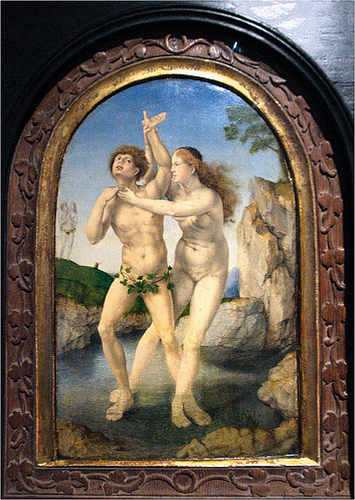

Hermaphroditus and Salmacis by Jan Gossaert (1520)

This painting of Hermaphroditus and Salmacis by Jan Gossaert illustrates just how much this theme resonated with later artists — especially in the Renaissance. (More about those next time!)

As you might imagine, Christianity was much more hostile to the concept of anything suggesting sexual ambiguity. But hold on! — not as hostile as you might think (given certain conditions). Let’s consider the phenomenon of the cross-dressing female saint.

A great example is St. Pelagia — also known as Margarito — who is kind of an archetype for the cross-dressing female saint. In one version of her story she is a beautiful dancing girl and prostitute who repents and converts to Christianity and dresses like a man.

St. Eugenia, another early Christian martyr, cross-dressed in order to join an all male religious community and later went on to become an abbot. Only when she was falsely accused of making sexual advances to another woman did she reveal her true sex.

St. Wilgefortis

My favorite, however, is St. Wilgefortis who is thought to have been bearded. This image incidentally of Saint Wilgefortis is in the chapel in Prague's Loreto Church.

Wilgefortis resisted marrying the king of Sicily — a man her father had chosen — preferring instead a contemplative Christian life. She prayed for deliverance — and as a result grew a long mustache and beard. Consequently, her suitor rejected her and her father had her crucified.

In some circles, St. Wilgefortis is considered the patron saint of married women who wish to be rid of their husbands.

There are enough similarities in these stories of cross-dressing female saints that some scholars have argued that they represented survivals of pagan practices — specifically of those surrounding Aphrodite of Cyprus — where women sacrificed to the goddess of love in men’s clothing and men in women’s.

As for examples of cross-dressing male saints there seem to be none but one might also argue that invariably higher status would have been accorded women who cross-dressed — but not men who would have lost status for doing so.

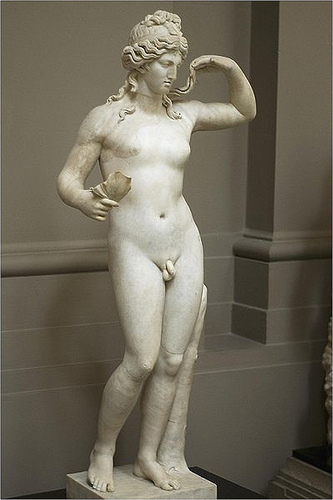

Aphrodite